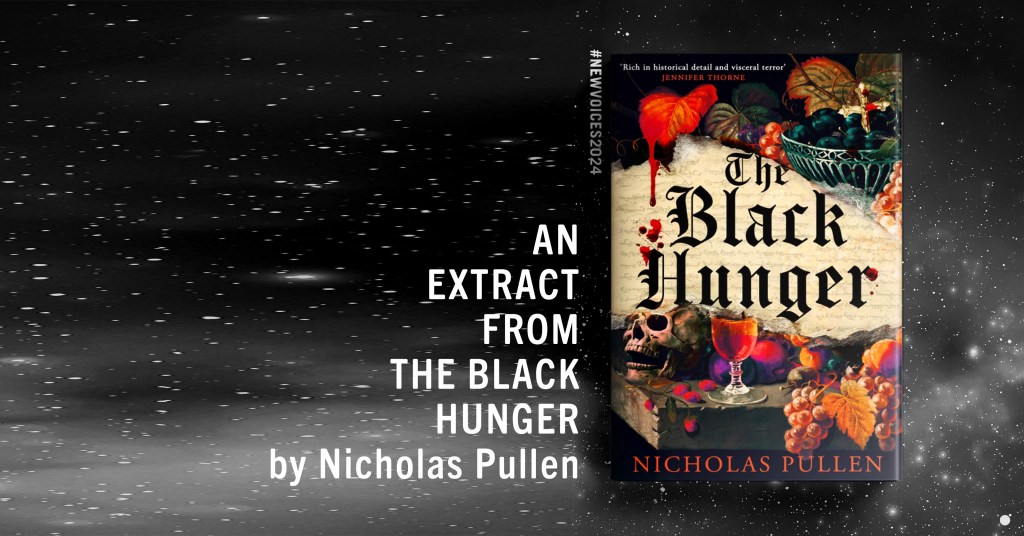

Read an Extract from The Black Hunger by Nicholas Pullen

THE BLACK HUNGER BY NICHOLAS PULLEN

‘A gothic masterpiece and a devastating exploration of humanity’s capacity for evil’ Sunyi Dean, author of The Book Eaters

John Sackville will soon be dead. Shadows writhe in the corners of his cell as he mourns the death of his secret lover and the gnawing hunger inside him grows impossible to ignore.

He must write his last testament before it is too late.

It is a story steeped in history and myth – a journey from stone circles in Scotland, to the barren wilderness of Ukraine where otherworldly creatures stalk the night, ending in the icy peaks of Tibet and Mongolia, where an ancient evil stirs . .

A spine-tingling, queer gothic horror debut where two men are drawn into an otherworldly spiral, and a journey that will only end when they reach the darkest part of the human soul. Perfect for fans of The Historian and Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell.

Read on to enjoy the first chapter!

CHAPTER ONE

18 February 1921

I do not have long now. I can feel it. It has crept over me so slowly that, at first, I was hardly aware of it, but it’s in my flesh now. A burning, tingling feeling, like when I was bitten by a spider as a child. Spreading through my limbs and my body, inexorably and painfully. I am outwardly in good health, despite the wound’s grey festering. But I know, and my minders know, that there is no forestalling the inevitable result. And I am always hungry.

The asylum is cold and grey; its stone walls seem to emanate a deeper, more lasting cold than the frigid wind and rain outside my barred window. The darkness is absolute, at all hours of the day. I have a private room at least, and do not have to mingle with the other inmates. That is a small mercy. I interact with no one at all, except my minders, and their clumsy attempts to get the truth from me are hardly companionship. I will never know companionship again. Garrett is dead.

I know what it is you want from me. And I will give it to you in my own time, and on my own terms. If this is to be my last testament, then damn your urgency. I do not fully believe you can stop what is coming now, anyway. But I will help you try. I will tell you what happened. You will have your intelligence, but I will tell my story.

And Garrett’s.

You don’t know who Garrett was. Or, rather, you don’t know who he was to me. No one did, so far as I can tell. No one even suspected until the end: for a decade. I’m astonished at having hidden a best friend, a brother, a lover in plain sight for all those too short years. And now I will never see him again. Now that you know, I find I do not much care what you think. I have days left to live, if I’m lucky, and have no time or patience for your disapproval or the disapproval of God, or the law, or society at large. How can you punish me now? You talk of sin, but not of love. You talk of disgust, but not of beauty. And the love we had for all those years was beautiful. And perhaps it would have been even more beautiful had it been allowed to flourish in the light. God, if He is interested at all in what Garrett and I did when we were alone, now has bigger problems than us.

My name is John Sackville, and I am the only son of the Earl of Dorset. I have no children, and so the line will die with me. I was born in 1888, and I was the only one of my parents’ children to reach adulthood. There were three boys and a girl before me, but they had died of various childhood diseases before I was born. By the time I was born, my parents were in their middle forties, and had long since resigned themselves to childlessness. I was an unexpected blessing that they seized upon fiercely, and I was the recipient of their entire affections; of all that was best in them.

I grew up on my father’s estate outside Lyme Regis. Most of my father’s peers had great, rambling estates and elaborate country man- sions full of pompous grandeur. My grandfather let his father’s ornate baroque palace go to ruin not long after he inherited it, and moved his family into a small manor house within our gift in the little vil- lage of Dalwood, just over the hill from the decaying old mansion. It was a quiet, unpretentious place. Clean and comfortable, and certainly spacious, but without grandiosity or pompous ornament. This was in keeping with my parents’ beliefs, for my grandfather had become a secret Quaker, and though my parents kept up the outward formalities of attendance at the Anglican Church, quietly, behind closed doors, they practised a kinder, gentler version of the faith of their fathers. Perhaps this is why they never judged me, even though I suspect, indeed am almost certain, that they knew.

My father had no interest in London, or politics, or society, or anything but managing his estates and raising his family and keep- ing to his religion. He kept an enormous diary and would spend the mornings beavering away at it in his study. He was also an amateur naturalist, and would go on long walks around the countryside, through the fruit orchards, often with me in tow, spotting birds and pressing flowers. My parents loved their version of God, loved each other, and they loved me, dearly. We could have spent our entire lives in Dalwood and never felt the need to leave.

And it was a pretty place, nestled in a glen, with enormous oak and chestnut trees shading a brook that flowed under a yellow stone bridge. The air was redolent with the smell of fruit from the orchards all around. All the houses, built in the same warm yellow stone, would glow in the late afternoon summer sunshine, and the sunlight would flash and dance through the leaves of the trees in the wind which carried a faint tang of the sea. The packed earth roads would be warm under my bare feet as I skipped across the bridge looking for chestnuts and oddly coloured rocks. By winter candlelight, as frost glazed the ancient windows, my mother would read me stories by the roaring fire in our parlour, and I would doze off to Walter Scott novels and old collections of Arthurian folk tales, my head in my mother’s lap. The village had a timelessness, as though nothing had changed there for hundreds of years, and nothing would change for hundreds of years to come. At Christmas I would be allowed a glass of elderberry wine, or golden cider from the local orchards, and we would make Christmas pudding from the fruits of our own trees. My mother would always remember where the coin had been placed, so invariably my portion contained it. Perhaps it was the accumulation of luck that allowed me to pass in polite society all these years. Perhaps it was what led me to Garrett.

We were near the same age, though Garrett was about a year my senior, which made him seem so much older at an age when nine months is an eternity. I first met him when my father engaged him to give me swimming lessons in the river that ran near our home. He had been born the son of one of my father’s tenants, a thin, taciturn, black-haired, man, with a dusting of a moustache, and a wife he did not seem to care for very much. Garrett and I grew up playing together in the village and in the fields and forests around it, and my father never made the slightest effort to curtail the friendship. Throughout our childhoods we were hardly aware of the class dif- ference between us. That cruel truth would be made plain to us later. In those early days it was hardly more than my gentle mockery of his ponderous, cumbersome West Country accent, which he never lost, in later life, despite everything that happened.

He grew up stocky, with flaming auburn hair, bright blue eyes that would crinkle into his face when he smiled, which he did often. He had dimpled, pudgy cheeks, a thick beard that came to him early, and no discernible resemblance to his father of any kind. By the time we were both fourteen, it was rather obvious. And to hide his shame, Garrett’s father would beat him with a belt, imagining all sorts of crimes that deserved such punishment. I found out this secret pain one evening the summer I turned fifteen. We were playing around in the vine-covered, collapsing ruins of my family’s old estate, and he broke down in tears and confessed everything his father was doing to torture him. He sat on a low stone wall and he buried his face in his hands, weeping in that choked, broken way some men do, as though they would rather die than be seen to weep. I put my arms around his shoulders, and I kissed him once on the forehead. It seemed the natural thing to do. He looked up at me in shock, and I realised what I had done. But before I could cover my instinctive action with some plausible indifference, he was kissing me. His cheeks were wet with his tears, his lips were dry and cracked and his face rubbed mine raw with its thick, bristly stubble, already grown back from the morning’s shave. But I kissed him back with all the passion I could muster from my frail frame.

It took us months to figure out the mechanics of love for men like us. Mostly in the ruins of the old estate where we knew we would never be disturbed. I would take him inside me, and my knees would be covered in red lines from the grass where I knelt. He would take me into his mouth, afterwards, when he was spent, and finish me then. But often I didn’t need him to. It was enough to have him inside me. Sometimes, as though he felt guilty, it would be his turn to kneel. And I would do it because I knew he enjoyed it, too. But I was happiest when I was beneath him. And afterwards we would lie naked in the grass in the gathering summer dusk, a blanket discarded beside us, bathed in each other’s sweat and with our arms draped around each other. I felt safe. I felt home.

My father had avoided sending me to boarding school as a child, as most children of my class were forced to do. The Empire relies for much of its strength on brutalising children in the system of organ- ised violence and torture that we call the Public School System. The children are torn from their parents’ sides, and thrown into a world of cold showers, casual cruelty and crushing loneliness, where they learn the delicate ropes of hierarchy and obedience, when to give, when to take, when to punish and when to accept punishment. They are stripped from love and safety and forged in the crucible of brutal conformity and rote Latin learning into good little psychopaths who can be trusted with the governance of the Empire. He put it off for as long as he could (most children were sent away before they were ten) and I had a succession of wonderful governesses and tutors, but eventually it couldn’t be postponed any longer. I cried when my father called me into his study and told me that I had to spend the next four years at Rugby School, far away in Warwickshire. He embraced me, and dried my tears, and told me that I would be home for Christmas, and that all would be well, and that he and my mother would always love me.

“Is there anything I can do that might make it easier, John? Anything at all?” I shook my head and sniffed. “Perhaps you’d like Garrett to come with you You’re allowed one servant, after all. I suspect he would do the job well, and he would remind you of home.” He looked at me rather significantly when he said this, and I felt a sinking feeling of discovery. But to this day I do not know if he knew or suspected anything at all, or if I merely imagined it. I suspect the former.

“Yes. I would like that.”

I told Garrett that evening as we sat together, dangling our legs over the little stone bridge in the centre of the village. I wanted to hold his hand, as I sometimes did when we were alone in the ruins, but we knew enough even then to know from the fiery sermons of the vicar that we could not do so where we might be seen. I was ter- rified that, despite everything, he would balk at going so far from the only home we’d ever known, but he only smiled and looked in my eyes, and said:

“I’d go anywhere, sir, so long as it’s with you.” When he called me sir it was with a quiet, gentle mockery that only I understood, and an ironic knowledge of how things really stood between us. It made my heart sing with the hilarity of it.

And so we went to Rugby. I lived in my rooms, and Garrett lived in the servants’ quarters, but he was with me in the evenings. We couldn’t do anything untoward. There was no privacy to be had. And Garrett and I learned quickly under the cruel mockery of the other students and the other servants to hide in public whatever intimacy we possessed from our childhoods.

But sometimes Garrett and I could contrive to be alone with one another. And after a while, with his pay Garrett rented a little room above a pub in town from a landlady who didn’t ask questions, and I would give him some of my allowance from Father to help with the rent, and we would be alone on Saturdays and Sundays. Sometimes for the whole day, if we were lucky. Garrett would tell me casually about the mockery he faced from the other servants, but after so many beatings from his father it did not faze him in the slightest, and he mocked their pomposity and their crude, Essex accents to me as viciously as they mocked him, to my raucous laughter. He was a talented mimic, and had a devastating wit.

I didn’t need to study. Mother had already drilled me in Latin and Greek, and I was well ahead of the other boys in my form. And when one day when we were sixteen Garrett expressed an interest in what I was learning, I began to tutor him myself, and smuggled him some textbooks from the lower forms, and before long he proved an astonishingly quick student, to whom languages, ancient and modern, came with uncanny ease. He eventually became a consid- erable classic in his own right. I admired him more and more as the years went by. I always will.

“If you’d been born with land, you’d be the talk of the school,” I wrapped my arms around his neck and pulled him away from his Virgil for a kiss. He smiled up at me.

“If I’d been born with land, I’d have been born far away from you, and I would never have known you at all, sir. There can only be one Lord of the Manor.”

“You don’t have to call me that when we’re alone.” I grinned.

“Don’t I . . . sir?” he grinned again. Then he pushed me away. “I guess that’s just the way of it. God doles out the titles before we’re born, and the rest of us suffer what we must.”

“I wish it wasn’t this way.” This was the first time we had ever addressed the subject directly.

“Wishing won’t make it so, now, will it sir? We have to live in the world we’ve got. And we’re happy enough, far as I can see. I could be in the workhouse, or back on David’s farm.” He shuddered. He had stopped calling his father anything but David a few years before.

“Still, it’s bloody stupid that you are where you are, and we are where we are. You’d have a brilliant career ahead of you.”

“Well, your career will just have to be brilliant enough for the both of us.” He stood up and pushed me against the wall. “As long as you and I always know the score . . . sir.” His breath was on my neck, and I was pinned against the coarse oak boards, panting with anticipation. He whispered in my ear:

“Pedicabo ego vos et irrumabo, sir.” Then he flipped me around, and with a quick pull at both of our belts he was in me, and I forgot all the injustice, the deception, the risk. He was in me, and that was all that mattered. It’s all that ever will. And you can keep your judgements to yourself.

Rugby, it turned out, had its share of degenerates like us. Lock that many vulnerable boys and corrupt old masters into a cloistered prison for long enough, and things will happen. But it had none of the tenderness and respect there that it had with Garrett and I. It was transactional. It was about power, and dominance, and cruelty. My relatively advanced age, my late arrival at the school and my title shielded me from the most dreadful duties of “fagging”, as they called it. But the younger boys had it tough. Organised rape has been a principle of building male hierarchies since Sparta. You learn, and are meant to absorb forever, that there is no place so private that your superiors may not intrude there. I was disgusted by it and took no part. Garrett became jealous at the mere suggestion that I had and flushed red with embarrassment and anger when we talked about it. I promised him that I cared only for him and would never avail myself of any privileges such a corrupt system might offer me. And I never did, for the four years I was there. The younger boys treated me with a great deal of respect for it, and by the time I left school I had everyone’s grudging admiration, if never their love, for my scholarly achievements, and for how I conducted myself.

I had one truly great teacher, Master Hornby, who has some bearing on my story. He was a stern old Northerner with massive, flared eyebrows and a shock of white hair over a glowering face. He was kind to me, in a gruff sort of way. I believe he saw how lonely I was, and he offered me scholarly companionship, along with a few other boys from the higher classics forms. We would get together on Thursday evenings to read Ausonius and Jordanes and Ammianus Marcellinus and some of the other, more obscure, late Roman authors.

I was drawn to late antiquity. There was a tremendous sense of possibility in everything I read from the third and fourth centuries ad. You could see the old world dying and a new one being born right on the page. The sad, aristocratic poets desperately aping Virgil and Cicero and awarding each other meaningless honours from a dead Republic as the barbarians set up camp all around them struck me as being inexpressibly tragic. Their ornate Latin was cloying and sweet, like Turkish Delight. Then there was the more muscular prose of the early Church Fathers; their fanaticism clear as a funeral bell, their language full of deadly purpose to exterminate the old, demon- haunted world and to usher in the Kingdom of Christ. As someone who often felt he might have been more able to be himself in the old, demon-haunted world, I rather resented it, though I admired their discipline and tenacity. Besides, one can only read Virgil and Cicero and Caesar so many times before one begins to tire of it. The problem with the classical texts is that there are only so many of them. There’s the later scholarship, I suppose, but most of it is worth less than the paper it’s printed on.

Hornby also taught Oriental Studies, though he had few takers for it. When he saw how bored I had become with Latin and Greek and the dead classics, he called me to his office one evening, and offered me a cup of tea, and changed the course of my life forever.

It was early evening, and the winter light was blood-red as it spilled through the window of his third-floor study, and a fire crackled under the mantel as we sat in high-backed chairs by the fire. He was blunt.

“You need a challenge, Sackville. Tell me, what do you know of India?” I told him that my mother had read me the Thousand and One Nights when I was young, which I supposed came from Persia, but that the strangeness of them, and the sense of a whole other cosmology underlying their construction, meant that I remembered them vividly.

“Good enough. How would you like to learn Sanskrit? And then modern Hindustani? Perhaps Urdu if we have the time. It’s a much more elegant language. And perhaps Tibetan, which has a power all its own. We have some time before you go to Oxford, and I think I can prepare you in what time we have.”

“For what, sir?”

“For Oxford, boy. You’ll go mad reading the Western classics. Your father has taught you well. There won’t be much you haven’t read. I’m recommending you to Dacre Winslow at Pembroke. He’s one of the foremost scholars on Buddhism in the Western world. I believe you and he will get along famously.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“I realise that you probably just want to go back to Dalwood and manage your father’s estates with him,” I grimaced slightly. I increasingly did not think I would want that. Garrett and I could never maintain discretion for long in Dalwood. Everyone would be desperately waiting for me to marry, and father children, and I dreaded the idea. “But I do believe it would be a terrible waste of your talents, John. You are capable of much more.”

“Thank you, sir. I will do my best.”

And for the rest of that last year of sixth form I focused on the basics of Sanskrit; its curious music and its even more curious elegant, ornate Brahmic script. I was fascinated from the very begin- ning. After two years I was able to construe, in a very basic sort of way, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana and the Upanishads and the four Vedas. I picked up a smattering of Urdu and Hindi, but I always struggled with Tibetan, finding its complex system of honorifics difficult to penetrate. Garrett was far better at it than I was.

Before I left for home for the summer, I received a letter from Dacre Winslow cordially introducing himself and informing me that, at Master Hornby’s express recommendation, he would be de- lighted to take me on as a pupil at Pembroke College, assuming I had not already accepted another place elsewhere, for the Michaelmas term of 1908.

Enough has been written of the beauty of Oxford. You can find adequate panegyrics to dreaming spires in any threepenny paperback. I don’t propose to add to their number. Go and see it for yourself if you’re so inclined. It won’t disappoint. For me, it will always be the scene of some of the happiest days of my life, but what is that to you? Make your own memories.

Of course, Garrett came with me, and my rank and title got me a lovely set of ground-floor rooms on Pembroke’s Old Quad, with an adjoining servant’s quarters, so Garrett became my scout, and he and I essentially lived together for the entire three years, in and out of college. In Rugby we had had our little rooms. But in a college it was much harder to find time to be alone together. My windows left little room for privacy. Mostly when we made love it was in Garrett’s tiny, windowless servant’s bedroom, and the room would stink of us for hours afterwards. But it was a delicious smell.

Garrett grew into a great bear of a man in those years. He kept his auburn hair and beard closely trimmed. His face was round and apple cheeked, and when he smiled it was a great toothy grin that split his face like a peach, and his eyes would crinkle and disappear. He was thick and burly with a broad chest, a hairy belly and big heavy arms and legs like tree trunks. It was the kind of weight that gives the impression of immense strength, and not of ill health. And, God, he was strong.

The other freshers were noisy and boisterous and frequently broke the windows of those unfortunate enough to have rooms on the ground floor. I avoided them, and for the most part they avoided me. I formed a small coterie of like-minded friends, and a few of us would get together on Saturdays for a luncheon, which sometimes, I’ll admit, got a little boozy. Once or twice I hosted one myself in our rooms, and Garrett would serve the food and pour the drinks for Yarmouth, Jones, Portishead and I, poker-faced and unsmiling. My eyes would follow him around the room, of course, but no one ever seemed to notice.

I did make one friend who has some bearing on my story, beyond vacuous reminiscence of Oxford days. I met him through my tutor, that first Michaelmas term.

Dr Dacre Winslow turned out to be in his late forties. Thin, tall, with a pleasant, long face and receding brown hair, he affected a little gold watch chain, but otherwise dressed much as you would expect a don to do: soberly and conservatively, all shabby gentility. His office was across the Old Quad from my own rooms, on the first floor, and at our first meeting I could look down and see Garrett clearing away the plates from breakfast in the morning sunlight. There was some preliminary chatter about how I was settling in and what I thought of the college, but once we were both comfortably seated on a pair of leather armchairs by the window, he cocked his head and smiled at me.

“So. What would you like to do?”

I was taken aback, and it must have shown on my face. Dacre narrowed his eyes and waited for my reply. The seconds ticked by on the grandfather clock in the corner of the study. I digested the implications.

“You mean we can do anything?”

“Yes, within reason. The Orient is rather large. Shall we look at ancient Persia? The Gupta Empire? The Mughals? Han China? Heian Japan?”

I hadn’t expected this at all. I was eighteen, and used to being told what to do and what to study. I had expected it to be like Rugby, where a rigorous, pre-determined course of study had existed for cen- turies before I got there and would exist for centuries afterwards. I hadn’t grasped that university meant intellectual freedom. It yawned like a dizzying abyss before me. I had to choose and did not know where to start.

“Well, I suppose I would like to look at Vedic India, and perhaps the Jain and Buddhist reformation.”

“Reformation?” I waited for him to laugh in my face. Instead he looked thoughtful. “Well, yes, I suppose it was not unlike a refor- mation. A time of upheaval and change, certainly. I see your point. Though it’s a rather more complex situation, and we have far fewer sources to hand.” That was unexpected. “Well, that will certainly make my life easier.” He drew a piece of paper from a folder on his desk.

“This is the reading list I usually give to first years. How is your Sanskrit? Passable? Good. It will improve as we go.” There was a knock on the door, and Dacre glanced at his watch. “Oh, impeccable timing. Come in!”

A boy about my own age entered the room. I was taken aback to see that he was of oriental extraction. He was tall and well-built, with short black hair, cut in European fashion, and a lithe, athletic body hidden beneath a Savile Row suit. His face was aristocratic, fine-boned, but friendly and pleasant, with heavily hooded eyes.

“Dr Winslow, I hope I’m not interrupting?” He glanced at me, cool, offhand.

“Not at all, Sid, please come in. I was hoping to introduce the two of you.” He entered. He was carrying a manuscript, which he handed to Dacre, who accepted it casually, with a nod of thanks.

“The translation is done. I trust you’ll let me know if it’s useful.”

“Yes, thank you, dear boy. This is John Sackville, the Lord Dalwood,” he said, indicating me. I stood up, hand outstretched.

“Pleased to meet you,” I said with a smile. He shook my hand. “And you are?”

“Sidkeong Tulku Namgyal,” he said. “But you can call me Sid. You might have a bit of trouble pronouncing the whole mouthful.” He smiled,

diffidently.

“Ha! I’m sure I’ll get the hang of it. I haven’t seen you around college yet. Where have you been keeping yourself?”

“Oh, I’m a year above you. I’m studying engineering and natural sciences, so I don’t think you’d have seen much of me, if you’re working with Dacre.”

“Right, you two can leave now, and get better acquainted,” said Dacre, and with a little wave of dismissal he turned his eyes to the manuscript Sid had handed him. We left his office, and descended the staircase to the Old Quad, and turned and regarded each other for a moment. There was an awkward silence.

“Pub?”

“Yes, pub.” And so we went down St Aldate’s to the Head of the River, and got ourselves some cider, finding a table overlooking the River Isis, watching the traffic flow back and forth across Folly Bridge. And that was how we began.

“So where are you from, then?” I asked.

“India,” he said. He offered no further explanation.

“Yes, but where in India? My guess is somewhere in the Himalayas? Maybe one of the princely states?”

“You’re a sharp one, you,” he said, smiling ironically. “I suppose you mean that I don’t look like the rest of the Indian students here.”

“Well, I wasn’t going to say so in so many words,” I stammered.

“It’s all right, it was a good guess.” He took a long sip of his cider, and looked pensive, like he was weighing up his response. “Yes, I’m from Ladakh. My father is a merchant there.”

“Quite a successful one, if he’s able to afford to send you to Pembroke.”

“Yes, he does quite well.”

“And you’re mostly studying the sciences?”

“Yes, it’s a matter of practicalities. I need to be able to return home with something useful to offer my people. There is much to learn from the British. If we’re ever to make something of India, or to become independent, we need to learn all we can from you, as long as this awkward arrangement of ours persists.”

“Makes good sense you wouldn’t be taking Oriental Studies,” I laughed. “What would there be for you to learn?” I cringe to think of how awkward and ham-fisted my attempts at humorously bridging the gap between our worlds was, but Sidkeong was accommodating, and he shot back with jokes of his own.

“Quite. I’ll have to go back to Ladakh and set up an institute of European studies, see if we can unravel the riddle of you people,” he grinned. I laughed.

“It is rather an awkward arrangement, as you say.”

“Who’s that professor who came out with that tripe a few years ago about how the British Empire had been acquired in a fit of absence of mind?” Sidkeong asked.

“Ugh, I believe it was John Seeley,” I said. “What a facile thing to say.”

“Too right,” said Sidkeong. I admired the idiomatic fluency of his English. Even his accent was purest Oxbridge. If it weren’t for the colour of his skin you’d have thought he was just another young English gentleman taking his ease by the river. “I don’t think anyone but the British could possibly believe that you had anything other than full presence of mind when you brought half the Asian conti- nent under your sway. But presence of mind is a tricky thing, that I’m not sure any European really has.”

“I suppose that’s the Buddhist in you?”

“Indeed, you people seem to think that if you pray very hard to Jesus, he’ll just give you all the answers, and grant you your wishes like some sort of Arab djinn.” I barked with laughter.

“And there’s more to it than that, you’d say?”

“I would. Perhaps if you knew how to meditate, you wouldn’t have absent-mindedly stumbled around the world snapping up territories and dispossessing people.” His voice was heavy with sarcasm.

“Quite,” I agreed, laughing. “Perhaps I should give it a try.”

“Meditation?” He raised his eyebrows.

“Why not? It seems silly to read all this Buddhist literature and just to treat it as an idle foreign curiosity. It seems to work for millions of people, there must be something to it.”

“How interesting that you should think so,” he said.

“It’s the thing that appeals to me about Buddhism,” I said, the cider making me rather loquacious. “It seems to deal with reality in a way that the Abrahamic faiths simply don’t. The Four Noble Truths seem to get to the core of it. Eventually I will get old, I will get sick, everyone I know will die, and then I will die. It seems the challenge must be to make peace with that, surely? Not to pray very hard to Jesus, and hope that in the end he will give me a biscuit.” Now Sidkeong laughed; an open, full-hearted laugh.

“Make sure the chaplain can’t hear you,” he said. “I must say, you’re an unconventional one, for an Englishman.”

“I hope so,” I said with sudden feeling.

“To the unconventional. And, if you have no objection, to the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha,” said Sidkeong with an ironic smile, raising his glass.

“To refuge,” I said. And we toasted each other.

There was very little formal instruction. I met with Dacre once a week to discuss the essay I had written based on research in the various libraries. Every day I would walk from Pembroke up St Aldate’s, down the High Street, and through Radcliffe Square to the Bodleian, or, more frequently, to the India Institute at the corner of Broad and Catte streets. At first, I would read in the Radcliffe Camera and have my books brought there, but as time went on I began to find it rather too pretentious and intimidating, with its classical curlicues and arching sky-blue dome. I found that most of the books I needed were in the library of the Indian Institute anyway, just up the road from the Camera, which was much more snug and utilitarian. I found myself a cozy little desk by a window looking out onto Broad Street, and I would read there, occasionally looking up to daydream and watch the crowds moving past the Sheldonian Theatre and the Clarendon Building through the large, mullioned windows.

Every day, around four o clock, I would leave and head to the King’s Arms or the Turf Tavern and have a pint of cider, to remind me of Dorset. On days I went to the Turf, where I was less likely to see fellow students, due to its slightly dubious reputation, Garrett would come and meet me, and we would sit in the beer garden and talk. About what I had learned that day. About how the college servants got on. About my more aristocratic acquaintances whom I had to deal with to keep up appearances, and their various foibles. I talked frequently of what I was learning, and Garrett soon shared my fascination with India and its religions and its traditions. The harder I attempted to explain to him how it was that the British had ended up ruling the entire Indian subcontinent, thousands of miles of ocean away from home, the harder it became to understand, let alone explain. Garrett was always insightful and could make me laugh as no one ever could. To all appearances we were just two students having a quiet drink and a laugh and enjoying each other’s company. Garrett’s accent wasn’t precisely refined, but he could easily have passed for an Exhibitioner: the working-class boys of great promise that the colleges would finance to remove them from the worlds they’d known and thrust them into a world they were entirely unprepared for, and in which they would never fully belong.

It wasn’t very prudent, I will admit. Only once, in Hilary term, were we surprised by someone from the college. We were in the back- beer garden in the cool of a rainy January evening, warming ourselves by one of the charcoal braziers, in the shadow of the old city walls, when Tom Kelso suddenly appeared. Drunk, as usual. He was the son of a Scottish laird and had a rather boorish reputation around the college. He stumbled up to us, a pint of ale in his hand.

“Sackville. What are you doing here? Never thought you’d stoop this low.” Garrett and I shared a quick glance. Kelso saw Garrett. “Aren’t you Sackville’s servant?” His eyes narrowed.

“Yes, sir, begging your pardon, sir.” Garrett camouflaged himself immediately and well.

“What’s going on?” I narrowed my own eyes in turn, and adopted my coldest, most supercilious manner.

“What business is that of yours?”

“God, that Quaker father of yours wants to abolish all notions of rank, does he? He lets you fraternise with the servants?”

“My father is a good judge of character, Kelso. Better than you. And Garrett is one of my oldest friends. I won’t pretend I don’t prefer his company to yours.”

Kelso blinked in surprise. “You . . . what do you mean?”

“I mean you’re drunk, and you’re meddling in something that does not concern you. I mean that you should take yourself off to some other gin hole or other rather quickly. Garrett and I are talking about old times.”

Kelso didn’t seem to know what to say. But it appeared he was inclined to take offence. I braced myself for a fight. But, instead, he took another pull on his ale, muttered something slurred and apologetic, and slunk back into the bar. Garrett and I looked at each other.

“That was dangerous, John. It wasn’t wise.” He only ever called me John in moments of danger.

“Was it? I find I don’t care all that much. Besides, he was absolutely six sheets to the wind. At worst, he’ll remember he saw us here tonight.”

“Still, wouldn’t it be better to pretend I were someone else?”

“How? You’re known around the college as my manservant. Nothing for it but to brazen it out.”

While I was outwardly confident, I will confess that I passed more than a few sleepless nights, waiting to be exposed. The consequences would have been dramatic and devastating. Certainly, I would have lost my place at Oxford, and Garrett and I would both have been prosecuted under gross indecency laws, and sentenced, if found guilty, to two years of prison and hard labour. The social ruin would have been permanent and lasting, and Garrett and I would never be able to resume our relationship again without suffering further legal action. I couldn’t bear the thought of never seeing him again, and certainly dreaded prison. It wasn’t until a month had passed that I really began to feel safe again, and our mutual fear somewhat clouded our relations until we could feel certain the danger had been avoided. But in the end it was. I never heard anything more about it. Kelso gave me strange looks for a while. I think he remembered that he’d seen something unusual, but I don’t think he ever put two and two together. Some scandals are preserved from exposure by their very unthinkability. And the privileged classes always give each other the benefit of the doubt.

There is one other instance, and one other encounter, in my second year, that has some bearing on future events, and that doubtless you wish me to relate the particulars of. One afternoon, in the library of the Indian Institute, I gained my first intimation of the existence of the Dhaumri Karoti, and a few days later, at the Oxford Union, I met Count Evgeni Vorontzoff for the first time.