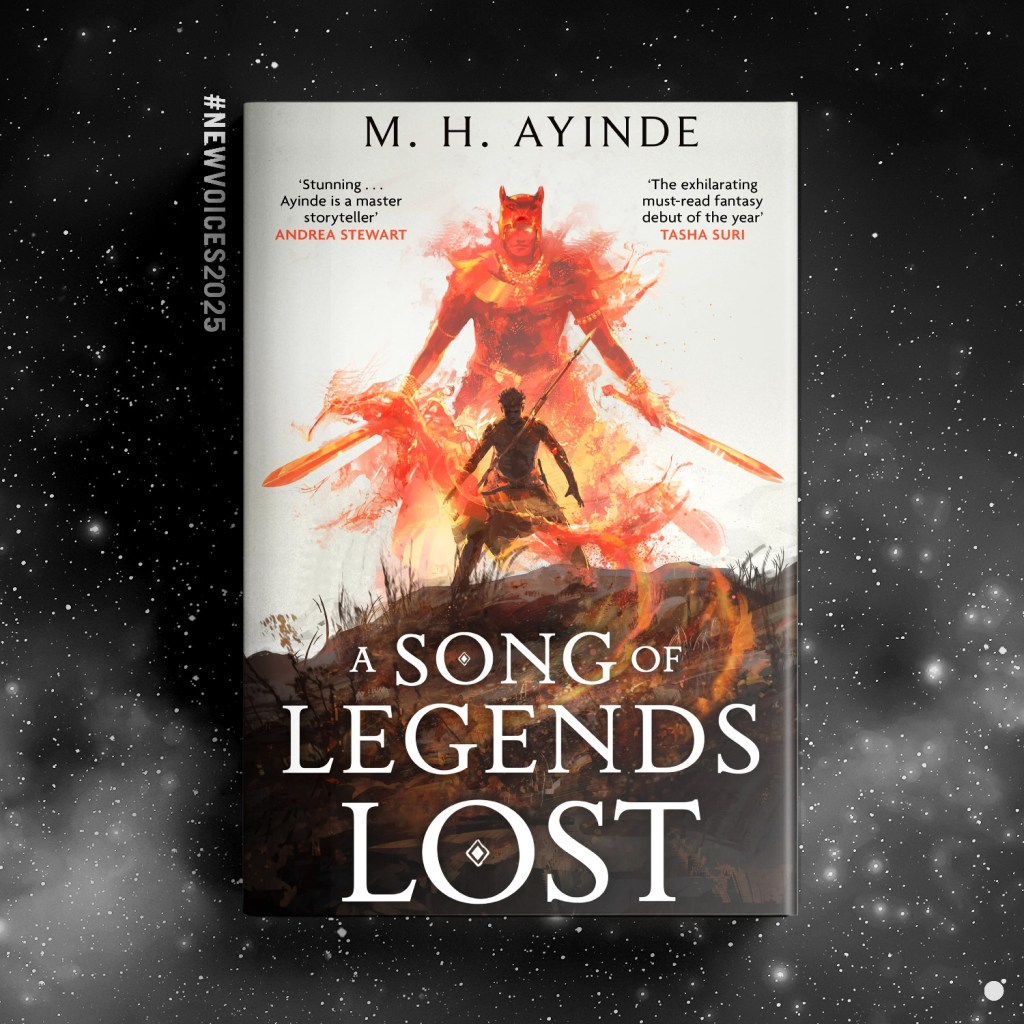

Read an extract from A Song of Legends Lost by M. H. Ayinde

A Song of Legends Lost

by M. H. Ayinde

A SONG OF REBELLION. A SONG OF WAR. A SONG OF LEGENDS LOST.

In the Nine Lands, only those of noble blood can summon the spirits of their ancestors to fight in battle. But when Temi, a commoner from the slums, accidentally invokes a powerful spirit, she finds it could hold the key to ending a centuries-long war.

But not everything that can be invoked is an ancestor. And some of the spirits that can be drawn from the ancestral realm are more dangerous than anyone can imagine.

Scroll down to read an extract from this unmissable debut.

PROLOGUE

Ngbali

Father Ngbali the Just, Arch Curator of the Sacred Order of the Twofold Path, Holy Guardian of the port town of Ninshasi, and staunch opponent of interruptions, was just biting into his plantain when the knock came.

‘What is it?’ he snapped.

‘Please, Father,’ his apprentice said from beyond the bamboo wall. ‘You’re needed on the beach.’

Ngbali closed his eyes. Needed on the beach. Usually, when he was needed on the beach, it was to identify a supposedly ancient artefact that transpired to be scrap metal washed over from the docks. Sometimes, it was to purify the waters of the borehole. Occasionally, it was to break up drunken arguments between younger monks. Rarely was it anything that necessitated interrupting a meal.

‘Mabasu, I would like you to deal with this, as a vital part of your training,’ Ngbali said. ‘You are an extremely capable soul, and I have every faith that the ancestors will guide you in your endeavour.’

He opened his mouth, the oil of the plantain glistening tantalisingly on his fingers, and was preparing to resume his breakfast when Mabasu’s tremulous voice struck up once more.

‘Holy Father, a shipwreck has washed ashore.’

‘Shipwreck?’

‘Yes, Your Holiness! Containing a techwork relic.’

Ngbali sighed. ‘Then bring the relic back to the monastery for Cleansing.’

‘Honoured Father, the relic is too large to carry. I could attempt the ritual of levitation, but the last time I tried that alone, if you recall, the damage to the nearby buildings—’

‘Very well!’ Ngbali said, slamming his hand on the table and standing. ‘I’m coming.’

He shoved the plantain into his mouth and crossed the room to retrieve his sacred staff from its spot by the bookshelf.

Outside, under the shade of the palms, Mabasu fell in beside him.

‘Thank you, Holy Father,’ he said. ‘I’ve never seen anything like it. The ship lies in near ruin, yet it contains a Scathed artefact of immense proportions!’

Mabasu was a spare, fawning sort of man, always wringing his hands and saying please and Your Holiness, but Ngbali had been dealing with souls like him since the day the monks scraped him off the streets of Nine Lords, a beggar- boy of six; he knew well the eager light in their eyes. These were souls who would not hesitate to climb over those they claimed to serve if they thought it might bring them to the attention of the royal monks or the king.

Ngbali harboured no such pretensions. He simply wished to live out the remainder of his days in this quiet backwater of the far south-east, eating plantain and cassava, reading the forgotten texts, and absolutely not identifying wondrous relics.

‘Tell me what you know,’ Ngbali said, licking his fingers.

‘Well, Your Holiness, some lowblood children were playing on the beach at dawn—’

‘Ah. It always starts with lowblood children playing. We must remember to outlaw that.’

‘Yes, Your Holiness. Well . . . they spotted the shipwreck, within which stood a magnificent relic of the purest blackglass. Upon its sides gleamed the ancient glyphs of the lost Scathed People, and the entire find exuded a terrifying energy, like something from beyond the pyre.’

‘And have you experienced this terrifying energy for yourself, Brother Mabasu?’

‘No, Your Holiness. I was too afraid to go near. Brothers Danadu and Ntalo are there now, fending off the townsfolk.’

Father Ngbali had assumed Mabasu was exaggerating when he claimed the relic was large, but as he descended the grassy hill onto the beach, Ngbali saw that he was not. Beyond the line of palms, where white sand met azure sea, lay a wrecked ship. It was a wonder the thing had made it ashore – the wood of the vessel was rotten and warped, and its cargo immense. And Mabasu had been right: against the ship’s portside gunwale lay a large wedge- shaped relic, its glossy contours shimmering like liquid midnight. Blackglass: that unfathomable material the Scathed had used to craft so much of their civilisation. The near end stood perhaps as tall as Ngbali himself, but the front tapered to a narrow point made for speed. It had no wheels, no windows, nor any doors, but Ngbali knew the meaning of the glyphs on its sleek side, glyphs that still glowed a brilliant blue, even after a hundred millennia.

‘It is a Scathed travelling carriage,’ Ngbali said. He had never seen one so well preserved. It would take years, perhaps decades, to Cleanse the entire thing. As he stalked nearer, pulling his feathered mask down over his face and waving his staff to clear a path through the knot of townsfolk that had gathered, he saw that the wall of the carriage had been shattered on one side. Its silvery innards glinted in the morning sun. Techwork: the cursed remnants of a civilisation best forgotten.

Brothers Danadu and Ntalo stood either side of the shipwreck, staffs gripped in their dark brown hands, feathered turaco masks hiding their faces. Their bead- skirts snapped in the morning breeze, and from the tense set of their tataued shoulders, Ngbali could see they were nervous.

‘Father Ngbali, there was a man here!’ Danadu said, his voice quavering.

‘What do you mean, a man?’

‘A man in the ship! He took something and ran off towards the docks.’

‘You mean there was a survivor? Well, get after him! Bring him back!’

‘Your Holiness, he will be long gone by—’

‘Then you had better run fast, hadn’t you?’

Ngbali turned back to the ruined ship as the youth sprinted off. The ornately painted name was so faded he could scarcely read it, but something tugged at his memory as he stared. He had seen this vessel before, on his travels, perhaps, in his younger days, when he had visited each of the invoker clans in their homelands and spent time in their palaces and castles . . .

Ngbali peered up at the break in the carriage wall. The blackglass there bowed outwards, as though something had forced its way free. Yet a shimmering light played across it – Forbidden energies, meant to repel. And within . . . within, he glimpsed travelling chests and two white objects perhaps six spans in length.

Bodies.

‘There are two shrouded bodies in there!’ Ngbali cried, recoiling.

‘Yes, Your Holiness!’ Ntalo replied. ‘We saw but dared not touch!’

‘You would not have been able to. Do you see the glowing light? This carriage is sealed by Forbidden means.’

‘Father, shall I send the townsfolk away?’ Mabasu said.

‘No,’ Ngbali said. ‘No, it is good to remind them that Scathed relics are not to be touched by untrained hands, and that only we who have dedicated our lives to Cleansing may have dealings with them. Let the people watch.’

Ngbali was still contemplating how he was going to get such a beast back up the hill, when it came to him. Where he had seen the ship before. And when. He had a flash of memory. Of crowds, lining the riverbank in the capital, Nine Lords, a thousand leagues from where he now stood. Of the reclusive king himself, come out to watch invokers from each of his warrior clans sailing off to the sort of pomp and fanfare that had not been seen in a generation. Of the hopes of every province in the Nine Lands resting on the invokers’ noble shoulders. That they would return with answers. Return with the greatest weapon ever created. Return with a way to end two millennia of war.

That had been five rains ago. And they hadn’t returned at all.

‘Mabasu, get back to the monastery. Contact Three Towers Palace. Tell them we have located the remnants of Invoker Jethar Mizito’s lost voyage.’

‘The – the palace, Holy Father?’ As if that were the most remarkable part of what Ngbali had just told him.

‘Yes, the palace! We need guidance from Grand High Curator Boleo. I know this ship. And he is not going to believe it.’

Ngbali regarded the blackglass carriage one final time. It resembled some great disembowelled sea creature, techwork veins hanging from its broken wall like entrails. Then he set to work. Lifting his staff, he began the sacred dance. As a youth, dancing had been his greatest skill; the fluidity as he leapt, the sharpness of his movements. His body wasn’t quite as obedient now as it had been then, but he could still put on a great show.

He began to chant, softly at first, in the Forbidden Tongue. His sacred staff grew warm in response. The crowd murmured in wonder, as they always did when they saw a monk in rapture. Many of them touched their foreheads to call for ancestral protection. Ngbali smiled beneath the calabash of his mask. He danced before the shipwreck, tapping his staff here and there, not letting them see the tiny, silver discs he slipped out of his robe and flicked up towards the deck. When enough of the discs had attached themselves to the carriage, he lifted his staff high, and as he did so, the carriage lifted too, rising from the deck like a bird taking flight.

Behind him, he heard gasps and cries of wonder. He chuckled to himself. Then he turned back towards the hill, and the carriage followed obediently.

‘Stand back!’ Ngbali declared. ‘You see before you a cursed relic of the most potent variety. The merest touch could summon a greyblood attack!’

‘Your Holiness!’ Danadu cried, appearing at his side. The young man’s chest heaved with exertion, sweat pooling between the muscles of his chest. ‘I’m sorry, Your Holiness. I couldn’t catch him.’

‘Catch who?’

‘The man! The one who ran from the ship! Perhaps he was just a thief? Or – or a vagrant, asleep in the wrong place?’

Ngbali sighed. Likely the man was lost to the grasslands now. But if he truly had been aboard the ship, letting him go would mean admitting that Ngbali the Just, Arch Curator of Ninshasi, had allowed possibly the most important soul in the realm to slip through his fingers. And that was a thing he could not abide.

‘No,’ Ngbali said. ‘No, that man was no vagrant. Send to the other monasteries. Put out a description – discreetly. We are going to find him. And we are going to recover what he took. Now somebody get me more plantain!’

PART ONE

Temi, Jinao

ONE

Temi

By the time Temi arrived, not even bones remained to send to the ancestors. She stood at the edge of the abandoned wharf, looking out across the small, muddy beach at what remained of her uncle’s boat. The hull was charred and blackened, as were the oars, and nothing moved within. No sign of her uncle and cousins. No sign of their cargo. And yet she had heard the screams as she ran down the dirt road. Had seen the strange green flames from the top of the hill.

Temi slipped down onto the riverbank, her bare feet sinking into cool mud. Beyond the boat, the River Ae crawled by, ruddy and sluggish as always. Great galleys slid through its waters, but nobody noticed this tiny, abandoned harbour in a ruined corner of the City of Nine Lords. Beyond the river wall on the far bank stood the shacks and huts of the district of Lordsgrave, and beyond those, like knives thrusting towards the sky, loomed the jagged crystal towers of the vanished Scathed.

Temi dropped to her knees. The curiously sweet tang of the fire caught in her throat as she blinked back tears. Four of her family were dead. An entire shipment of their cargo was lost. Six moons’ earnings had been taken by the flames. And the worst part was the driving rain would turn whatever ashes remained to sludge. She’d have nothing left of her cousins to burn on the pyre. Nothing to send on to the ancestral realm.

‘This was no accident,’ said a voice behind her.

Temi turned to see an old woman squatting in the mud. The many layers of her linen robes were plastered to her portly frame. At first glance, she resembled a nun – the bald head, the tataued feet – but the rings on her fingers and the crystal at her throat told a different tale.

‘Do I know you, Old Auntie?’ Temi said. Few souls came to the abandoned harbour. Surely this woman had heard the screams too, had smelt the strange, sweet smoke? And yet the smile she offered Temi was calm.

‘No,’ the crone said. ‘But I simply couldn’t walk by such terrible grief. Who were they, these poor souls?’

Temi drew in a shaking breath and unclenched her fists. ‘Relatives,’ she said. ‘Cousins, from Jebba Province. Weren’t close family, but they’re family still. What’s it to you, anyway?’

‘No ordinary fire could do this,’ the crone said, nodding towards the ruined boat. ‘What natural flame turns bone to ash but leaves the wood beneath merely charred? And in these rains! No, someone powerful has done this, child. Someone who wanted them gone.’

‘They never hurt nobody,’ Temi muttered. ‘They’re just traders.’

‘Traders, eh? Docking out here, so far from the market?’ The crone settled down in the mud, the rain sliding off her bald head in sheets. ‘You know, when I was a girl, this part of the river was used by smugglers. The Ae is the lifeblood of our great City of Nine Lords, and the spine of the Nine Lands. All sorts of things travel up its poisoned waters. Mind telling me what it was your family traded in?’

Temi looked away. ‘That ain’t your concern, Old Auntie.’ Likely the old woman was simply a curious traveller – there were enough of those in Lordsgrave. But the ancestors turned from souls who were loose with their tongues.

The crone stared thoughtfully at the wreckage. ‘Such a tragedy,’ she muttered. Then she pushed to her feet and set to opening the pack that stood beside her. ‘You’ll never get a spirit wood fire going in this. By the time the rains stop, everything will be washed away. I heard a story once, about a man who drowned. Swept out on the Ae during a storm. He was never seen again. His family had no body to burn, and so he did not return to the ancestors. When his wife died, though their children burned her body, her spirit lingered, searching for him still. Do you wish to remain forever roaming the city, seeking the bodies of your lost kin?’ She jerked her chin towards the river. ‘Spirit wood won’t burn in this, but I have something better.’

Temi couldn’t muster up the energy to question, and so she knelt silently as the crone set to work, her wrapper clinging to her legs, her braids heavy with the rain. The crone hitched up her skirts and darted about the blackened boat, sprinkling something from a pouch in her hand. It looked like sawdust to Temi, and much of it blew away in the wind, but some fell upon the mud and shallows, sparkling like tiny jewels.

Soon, the old woman stood rubbing her gnarled hands and removing her outer robe. The body beneath, in its closeclothes, was wholesomely round and soft bellied. As rain slid out of the grey sky, the crone danced, hands lifting and dropping as she chanted in the Forbidden Tongue. Temi watched her, feeling numb, until she heard a shuffling at her back.

She turned, expecting to see a lizard or a rat, but it was a cat; a scrawny thing hiding in the old woman’s pack. Temi held out her hand instinctively, but the creature hissed at her and flinched away. ‘Well fuck you too,’ Temi muttered, and turned back.

The old woman had worked herself up into a frenzy. Her eyes rolled, and her arms and legs jerked as she danced. Temi was just wondering whether she should say something to stop the crone before she gave herself a seizure, when the dancing ceased, and the crone dropped her hands, and as she did so, a perfect circle of green fire rushed to life around the ruined boat.

Temi scrambled backwards in surprise as the keen green flames flared and then softened. Now, a merry ring surrounded Uncle Leke’s boat. Neither the wind nor the driving rain seemed to touch it. Even the ruddy waters of the Ae could not wash it away. It was as irrepressible as the City of Nine Lords itself.

‘Oh, ancestors!’ the crone intoned, lifting her hands to the skies.

‘Oh, ancestors, please guide your children . . . What were their names?’

‘Leke,’ Temi said, her voice catching. Who else had been planning to come with him this time? ‘Raluwa. Abeni. Sede.’

‘Please guide your sweet children, Leke, Raluwa, Abeni and Sede, safely back to you, oh, ancestors. Guide their spirits beyond the pyre and into your realm, that they might be reunited with you for all eternity. Let the tears of those they leave behind serve as an offering, and proof of their worth.’

Temi heard the cat shuffling behind her again as the crone hobbled over, eyes fever bright. ‘It is done,’ she said, squatting down. ‘They have crossed. They will return to those they loved.’ She squeezed Temi’s shoulder.

‘What about the spirit wood?’ Temi said.

The crone smiled. ‘You see before you an ancestral circle formed from the shavings of a very rare kind of techwork. It is called Dust of Ancestral Light.’ She eyed Temi. ‘Does that trouble you? I assure you, it has been Cleansed.’

‘Techwork, is it?’ Temi said.

‘Just so.’

‘But you’ve made it safe for me. How kind.’

‘Think nothing of it, my child.’

‘Just one thing, though.’ Temi grabbed the woman’s wrist. Held her fast. ‘There’s no such thing as Dust of Ancestral Light. And you’re a fucking liar.’

The crone’s face hardened. ‘Traders, were they?’

‘Yes, traders. And we know a thing or two about Scathed relics. You can’t use techwork to send souls to the ancestral realm.’

‘Such ingratitude,’ the crone muttered, trying to extract her arm.

‘Why would you want to trick me?’ Temi said, voice rising with her temper. ‘I’m sitting here looking at the ashes of my family, and you come serving up this shit. What do—’ She heard the shuffling again and turned around to see the cat creeping towards the crone’s pack. In its mouth was a coin. Her coin. Part of the payment that had been in her satchel.

Temi dived for the crone’s pack; tore it open. There lay three more golden suns. There lay little Maiwo’s beaded necklace, a gift for Uncle Leke.

‘You thief!’ Temi cried, grabbing the woman’s arm again.

The crone snorted. ‘You ungrateful brat. It was a small price to pay for the peace that I was about to give you.’

‘A peace built on lies!’

‘Let go of me or you shall regret we ever met.’

‘I already do!’ Temi shouted. She glanced at the pack. ‘Where’s the rest of my money?’

‘What money?’

Temi tightened her grip. ‘Give it back, or ancestors help me, I’ll take it from you.’

‘Oh no you won’t,’ the crone said, touching Temi’s free arm with a sickening smile. Something sharp bit into Temi’s skin.

‘Ow!’ Temi cried, releasing the crone. A perfect circle of blood welled in the brown flesh of her left arm, next to her family tatau. ‘You cut me!’

‘Yes, and that’s not all,’ the crone snarled. She lifted her hands. One of her many rings began to glow. ‘I place a curse upon you!’

‘Oh, please—’

‘I place a curse upon you, Temi of the City of Nine Lords; Temi of the Arrant Hill bakers—’

‘How do you know my name?’

‘I curse you! Now, and forevermore!’

The crone began to shake, her eyes rolling up, her lips quivering with unspoken words. The ring – blackglass set with a red gem – glowed more brightly, pulsing ever faster.

‘I grew up in Lordsgrave, witch,’ Temi said. ‘You can’t scare the likes of me.’

But then the light from the ring flared, and a great force knocked Temi backwards, and all was darkness and silence.

Temi woke chilled to her core and with a dull throbbing in the back of her head. For a moment, she wondered why her brother had left the window open. Then she remembered. The river. The boat. The ashes.

Temi sat up, rubbing her head. The sky beyond the line of buildings was a rich blue, the remaining clouds tinged with the familiar golden glow that emanated from the king’s palace at the heart of the city. Mercifully, the rains had stopped. Traffic crawled by on the river beyond.

Temi groaned and rolled onto all fours, trying to piece together what had happened. Then her hand touched something soft, and she remembered the crone. No; the spirit witch – for that was surely what she was. A nun cast out by her peers for dabbling in techwork. To her surprise, the old woman lay on her back in the mud, eyes open, mouth open, arms spread wide.

‘Don’t play dead,’ Temi muttered, reaching for her satchel. The witch’s pack lay a few paces away. Temi could still see the curve of Maiwo’s necklace in the half- light. She crawled over and took it back, and her coins too. Then she turned to the witch.

The woman lay unchanged. Tentatively, Temi reached out and poked the woman’s hand. Then touched her again, more forcefully this time.

The witch sat up, drawing in a great raking breath. Her eyes had rolled back, but she turned towards Temi and croaked, ‘The ancestors have spoken! The king must fall by your hand!’

Then a terrible choking gripped her, and she clawed at her throat before collapsing back where she had lain only moments before.

‘Shit,’ Temi muttered.

She watched, wondering for a moment if the witch was playing another trick: trying to escape through feigned death. But as she stared at the crone’s chest, looking for movement, counting her own breaths, it became clear. The old woman would never stand again. How she could simply have dropped down dead, Temi could not imagine, and wasn’t particularly inclined to. Perhaps, in her rapture, the woman’s heart had given up. Or perhaps Leke and her cousins truly had crossed the pyre and had sent the witch her death as punishment for her misuse of their names. It didn’t matter. What mattered was that someone had murdered four of her kin, and the last thing Temi needed was to be found at a well-known smuggling cove with a cooling corpse beside her.

She checked the boat one last time, just to be sure. Perhaps she’d been wrong. Perhaps they had swum to safety. But no; there among the blackened sludge was Leke’s single gold tooth. She scooped it up, along with the sludgy ashes that remained, and deposited the lot in her satchel. Maybe there would be enough there to burn; whatever the witch had claimed, she could still try.

Something nudged against her leg. Temi looked down to see the witch’s strange cat. It mewled piteously at her.

‘You two- faced little shit,’ Temi muttered. But still, she held out her hand and let it lick her with a hot, rough tongue. Perhaps it saw in her a kindred spirit. They were both grieving now. But when she looked more closely, she saw it was no normal cat. Beneath its matted grey fur, she glimpsed blinking lights . . . A twist of metal where the outer skin had peeled away. This was no cat, not truly. This was something else. Temi lifted her foot. It would be a simple thing, just to bring her heel down. To grind the creature’s glowing eyes into the mud. It was a grey-blood. A tool of the enemy. A destroyer of civilisations. It was her duty to rid the Nine Lands of it.

Temi sighed. ‘Follow me if you like,’ she said, pulling her satchel full of ancestors over her head. ‘I won’t stop you.’ And she set off home.

At sunset, Sister Relina the Humble, High Shadedaughter of the Eighth Circle of Enlightenment, sat up in the muddy darkness. She drew in a painful breath and blinked the moisture back into her eyes. Her pack still lay where she’d left it – the foolish girl hadn’t thought to take it with her. But the techwork abomination was gone. That was something, at least.

Sister Relina lifted her hands, closed her eyes, and muttered under her breath. She touched the sacred jewel embedded in her skull and called softly to the ancestors to send her words to the Holy Mother.

And presently, the ancestors answered.

[Speak,] the ancestors said. [The Holy Mother is listening.]

‘Your Holiness,’ Relina said. ‘It is done. I have prepared the one who will bring down the king.’

Good, came the reply. Now let us hope that we have acted in time.